Science Correspondent, BBC News

Smithsonian

SmithsonianScientists have discovered a new pterosaur – a flying reptile that surpasses dinosaurs, more than 200 million years ago.

The jawbone of ancient reptiles was unearthed back in 2011, but modern scanning techniques have now revealed details that suggest it belongs to a new species in science.

The research team was led by scientists at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and named the organism Eotephradactylus McIntireae, meaning “Ash Winged Dawn Goddess.”

It is a reference to volcanic ash that helps preserve its bones in ancient riverbeds.

Suzanne McIntire

Suzanne McIntireThe details found are Published in the Proceedings of the Journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

It is now believed to be about 209 million years old, and it is the earliest pterosaur discovered in North America.

“The bones of the Triassic pterosaurs are small, thin, and usually hollow, and are therefore destroyed before fossilization,” Dr. Kligman explained.

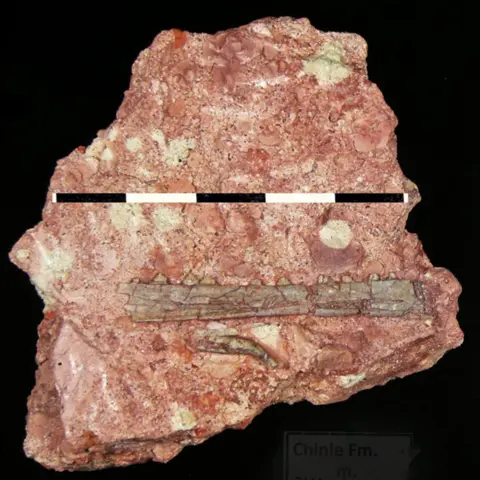

The site of this discovery is a fossil bed in an ancient rocky desert landscape in Petrified Forest National Park.

More than 200 million years ago, the place was a riverbed, when sediments gradually became trapped and preserved bones, scales and other evidence of life.

The river runs through the central region of the Pangia supercontinent, which is formed from the entire Earth’s land.

The jaw of the pterosaur is just part of the collection of fossils found at the same site, including bones, teeth, fish scales, and even fossil poop (also known as coprolites).

“Our ability to identify winghound bones in (these ancient) river sediments suggests that there may be other similar sediments in Triassic rocks around the world, and may also retain winghound bones,” Dr. Kligman said.

Ben Kligman

Ben KligmanStudying pterosaur teeth also provides clues about the winged reptiles the size of seagulls will eat.

“Their skill is unusually high in wear,” explains Dr. Krigmann, which suggests that the pterosaurs are feeding on things in hard body parts. ”

He told BBC News that the most likely prey was primitive fish that could have been covered with armor of bone scales.

The site of the discovery retains a “snapshot” of an ecosystem in which now extinct animals, including giant amphibians and ancient armored crocodile relatives, live with animals we can recognize today, including frogs and turtles.

Dr. Kligman said the fossil bed retains evidence of the “transition” of evolution 200 million years ago.

“We see groups that later lived with older animals (no) brought it beyond the Triassic.

“Fossil beds like this allow us to be sure that all these animals actually live together.”