Mexican, Central America and Cuba correspondent

BBC

BBCAfter the 30th month of rain, townspeople in De Conchos, San Francisco, Chihuahua, northern Mexico, gathered to plea for a divine intervention.

On the coast of Lake Toronto, the reservoir behind the state’s most important dam – called La Boquilla, a pastor led local farmers to ride horses and their families to pray that once part of the lake, the water retreats to the key level of today, the stone ground under their feet.

Rafael Betance has a head, who volunteered to monitor the State Water Authority for 35 years.

“It should all be underwater,” he said.

“The last time the dam was full and caused a tiny spill was in 2017,” Mr. Bets recalled. “Since then, it has decreased in years.

“Currently, we are currently below 26.52 meters of high water volume, less than 14% of its capacity.”

No wonder the local community is begging for rain in heaven. Nevertheless, few expect any relaxation from the brutal drought and the stuffy 42 degrees Celsius (107.6f) heating.

Now, a long-term dispute with Texas about scarce resources threatens ugly.

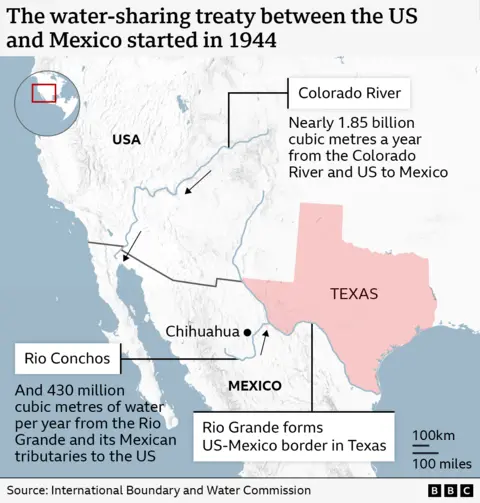

Under the terms of the 1944 water sharing agreement, Mexico had to send 430 million cubic meters of water from Rio Grande to the United States every year.

Water is a system of shared dams owned and operated by the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) through a tributary channel system that oversees and regulates water sharing between two neighbors.

In return, the United States sent its own larger allocation (nearly 1.85 billion cubic meters per year) from the Colorado River to supply the Mexican border cities of Tijuana and Mexico Island.

Mexico owes money and has not kept up with the water for most of the 21st century.

Under pressure from Republican lawmakers in Texas, the Trump administration warned Mexico to detain water from the Colorado River unless it fulfills its obligations under the 81-year-old treaty.

In April, on his Truth Society account, U.S. President Donald Trump accused Mexico of “stealing” water and threatened to continue escalating to “tariffs, even sanctions” until Mexico sends what Texas owes. Nonetheless, when will this revenge happen to him, he has no solid deadline.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum acknowledged Mexico’s shortages but put forward a more reconciliational tone.

Since then, Mexico has transferred the initial 75 million cubic meters of water to the United States through its common dam Amistad (located at the border), but that only accounts for a small portion of the approximately 1.5 billion cubic meters of Mexico’s outstanding debt.

Feelings about cross-border water sharing can be dangerous: In September 2020, two Mexicans were killed in a clash with La Boquilla Sluice Gates’ National Guard when farmers tried to stop water from redirecting.

In acute drought, the general view in Chihuahua is “you can’t take it from something you don’t have”, said local expert Rafael Betance.

But that didn’t help Brian Jones watering.

The fourth generation of farmers in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas, have grown only half of the farms over the past three years because he doesn’t have enough irrigation water.

“We’ve been fighting Mexico because they haven’t reached a part of the deal yet,” he said. “What we’re asking for is what the reason is under the treaty, nothing extra.”

Mr. Jones also objected to the scope of the Chihuahua issue. He believes that in October 2022, the state received enough water to share, but released “complete zero” to the United States, accusing his neighbor of “hoarding water and using it to grow crops to compete with us.”

The Mexican side farmers read the agreement differently. They say that only when Mexico can meet its needs will tether them to deliver water north, and thinks that the ongoing drought in Chihuahua means there is not too much available.

In addition to water shortage, there is also debate about agricultural efficiency.

Walnut and alfalfa are two major crops in the Rio Conchos Valley in Chihuahua, both of which require substantial watering – walnut trees require an average of 250 liters per day.

Traditionally, Mexican farmers simply flooded the fields with water from the irrigation passage. Driving around the valley, it was soon seen that walnut trees were sitting in shallow pools, water flowing in through the open pipes.

The complaint in Texas is obvious: This practice is a waste and can easily avoid the use of more responsible and sustainable agricultural methods.

As Jaime Ramirez walked through his walnut woods, the former mayor of San Francisco de Conchos showed me how his modern sprinkler system ensures that his walnut trees are properly watered throughout the year without wasting valuable resources.

“With sprinklers, we use 60% of the flooded fields,” he said. The system also means they can be watered less, which is especially useful when Rio Conchos are too low to allow local irrigation.

However, Mr. Ramirez easily admits that some of his neighbors were not so serious. As the local mayor, he urged to understand.

He said some people did not use the sprinkler method due to the cost of setting up costs. He tried to show other farmers that it would be cheaper in the long run, saving energy and water costs.

But farmers in Texas must also understand that their Chihuahua counterparts face existing threats.

“This is a desert area and rains are not coming. If there is no rain this year, then there will be no agriculture left next year. All available water must be preserved as drinking water for humans,” he warned.

Many in northern Mexico believe that the 1944 moisture sharing treaty is no longer suitable for purpose. Mr Ramirez believes that the conditions eighty years ago may have been sufficient, but it failed to adapt to time or properly explain the damage to population growth or climate change.

Texas farmer Brian Jones returned to the border and said the agreement has been tested by time and should still be respected.

“When my grandfather ploughed, the treaty was signed. It was through my grandfather, my father and now,” he said.

“Now, we’re seeing Mexico not complying. There’s a farm where I can only plant half of the ground because I don’t have irrigation water.”

He added that Trump’s stronger stance makes local farmers “in our steps” a Pep.

Meanwhile, the drought not only hurts agriculture in Chihuahua.

Mr. Bets said that with the levels of Lake Toronto so low, the remaining water in the reservoir is heating at a rare rate and bringing potential disasters to marine life to sustain a once-explosive tourism industry.

Mr. Betters said the prospect of the valley was not this terrible, and he spent his entire time carefully documenting the ups and downs of the lake. He reflected: “Praying for the rain is what we are left.”

Other reports from Angelica Casas.