BBC News

BBC

BBCEvery morning, Rosa Chamami wakes up and licks the cardboard pieces in the makeshift stove in the yard.

The box she brought home once contained 800,000 high-tech solar panels. Now, they burned her fire.

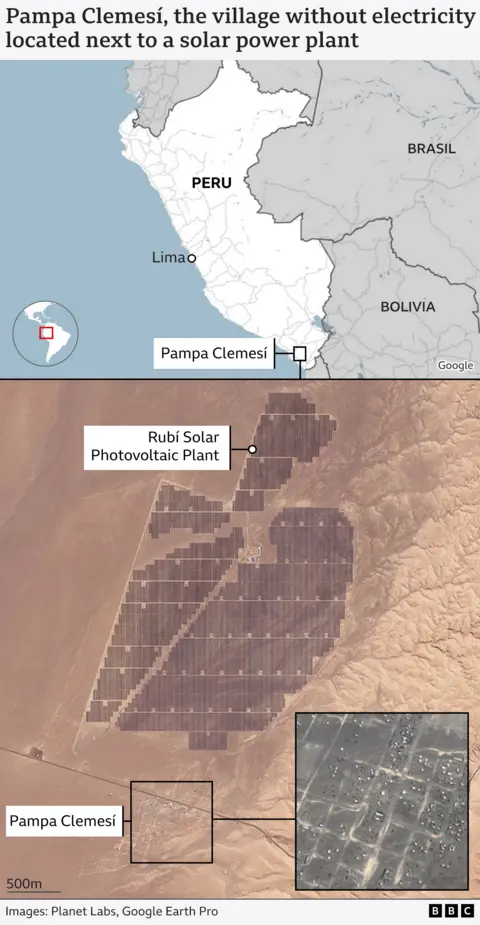

Between 2018 and 2024, the panels were installed in Rubí and Clemesí, two large solar power plants in the Moquegua region of Peru, located about 1,000 kilometers south of the capital of Lima. Together, they form the country’s largest solar complex and one of the largest solar complexes in Latin America.

From her home in Pampa Clemesí’s tiny settlement, Rosa can see a row of panels glowing under white floodlights. The Rubí plant is only 600 meters.

However, her home – and elsewhere in her village – is still in the dark, not related to the grid where the plants blend.

Electricity in the sun, but not at home

None of the 150 residents of Pampa Clemesí have access to the National Power Grid.

Rubí operator Orygen donated some solar panels, but most people can’t afford the batteries and converters needed to make them work. At night, they use torches, or just live in the darkness.

The paradox is shocking: RubíSolar power plant produces about 440 GWH per year, enough to power 351,000 households. Moquegua, where the plant is located, is an ideal place for solar energy, receiving more than 3,200 hours of sunlight each year, more than most countries.

This contradiction has become even more acute in a country currently experiencing a renewable energy boom.

In 2024 alone, renewable energy generation has increased by 96%. Solar and wind energy depend heavily on copper due to their high conductivity – Peru is the world’s second largest producer.

“In Peru, the system is designed around profitability. There is no effort to connect sparsely populated areas,” explains Carlos Godillo, an energy expert at Santa Maria University in Arequipa.

Orygen said it has fulfilled its responsibilities.

Marco Fragale, executive director of Orygen in Peru, told BBC News Mundo, BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language service.

Fragale added that nearly 4,000 meters of underground cable were installed to provide power cords for the village. He said the $800,000 investment has been completed.

But the lights are still not on.

The final step in connecting the new line to individual houses is the responsibility of the government. According to the plan, the Ministry of Mines and Energy must lay about two kilometers of wiring. Work is scheduled to begin in March 2025, but has not yet begun.

BBC News Mundo tried to contact the Department of Mining and Energy but received no response.

Daily basic struggle

Rosa’s small house has no sockets.

Every day, she walks around the village, hoping someone can save some electricity to charge her phone.

“It’s essential,” she said, explaining that she needed the device to keep in touch with her family near the Bolivian border.

One of the few people who can help is Rubén Pongo. In his larger home – with patio and several rooms, a group of spotted hens fight for the roof space between solar panels.

“The company donated solar panels to most villagers,” he said. “But I had to buy the batteries, converters and cables myself — and pay for the installation.”

Rubén owns the only thing others dream of: the refrigerator. But it can only run for up to 10 hours a day, but on cloudy days, it doesn’t.

He helped build the Rubí plants, and later worked on maintenance and cleaned the panels. Today, he manages the warehouse, and even though the factory is across the street, he is driven to work by the company.

Peruvian law prohibits walking across the Pan-American expressway.

From his roof, Rubén pointed to a group of glowing buildings in the distance.

“That’s the substation for plants,” he said. “It looks like a town that is ignited.”

A long wait

Residents began to settle in Pampa Clemesí in the early 2000s. Among them is Pedro Chará, 70. He watched the 500,000-PanelRubí plant almost rise.

Much of the village is built from factory-destroyed materials. Even their beds come from scrap wood, Pedro said.

There is no water supply system, no sewage, no garbage collection. The village used to have 500 residents, but due to scarce infrastructure, most of the remaining residents – especially during the 19th pandemic.

“Sometimes, after waiting for so long and fighting for water and electricity, you just want to die. That’s it. It’s almost dead.”

Torchlight’s Dinner

Rosa rushed to her aunt’s house, hoping to catch the sun. Tonight, she is serving dinner to a small group of neighbors.

In the kitchen, a gas stove heats the kettle. Their only light is a solar torch. Dinner was sweet tea and fried dough.

“We only eat what we can keep at room temperature,” Rosa said.

Without refrigeration, protein-rich foods are difficult to store.

Fresh produce takes 40 minutes to get to Moquegua if they can afford it.

“But we don’t have the money to take the bus every day.”

Without electricity, many people in Latin America use firewood or kerosene to cook the risk of respiratory diseases.

In Pampa Clemesí, residents use gasoline when they are affordable-wood when they cannot.

They pray through the torch for food, shelter and water, and then eat silently. It was 7pm, their final event. No phone number. No TV.

“The only thing we have is these little torches,” Rosa said. “They don’t perform much, but at least we can see the bed.”

“If we had electricity, people would come back,” Pedro said. “We stayed because we had no choice. But with the light, we could build a future.”

The breeze blows the desert streets and lifts up the sand. A layer of dust settled on the lamp posts in the main square, waiting for installation. Wind signals indicate dusk is coming – there will be no light soon.

For those without solar panels, such as Rosa and Pedro, the darkness stretches to the sunrise. They hope that the government will behave one day, too.

Like many nights before, they prepare for another night without light.

But why do they still live here?

“Because of the sun,” Rosa replied without hesitation.

“We always have sunshine here.”