Even after decades of looking at cells, biologists still find surprises.

In twisting, researchers at the University of Virginia and the National Institutes of Health have discovered a new organel, called Hemifusom. This small membrane bound structure serves as a cell recycling center and may hold the key to treating several genetic diseases. The research has been published in Natural communications.

“This is how to discover a new recycle center in the cell,” co -author Seham Ebrahim, a biophysicist at the University of Virginia, said in A Statement. “We think the hemifusome helps to manage as cellular packages and process materials, and when this process is hindering, it may contribute to diseases that affect many systems in the body.”

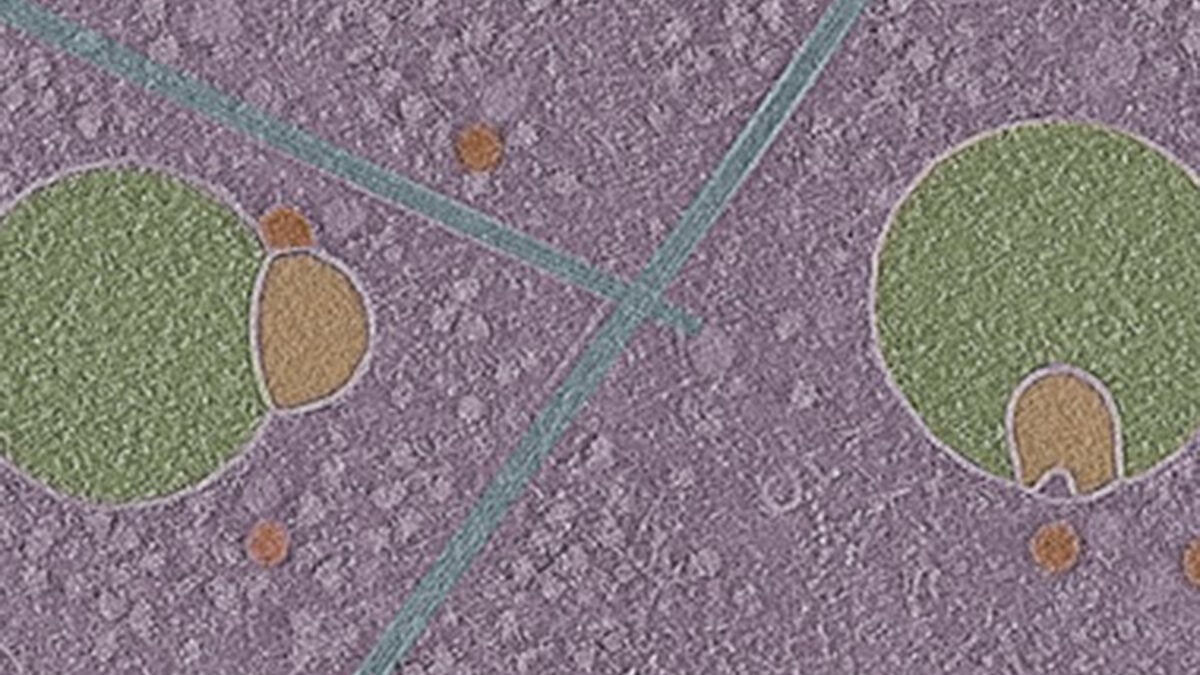

Scientists have not previously identified the structure because it only appears when needed. But thanks to a cry-electron-tomography image technique, which flashes cells and captures them in 3D and in near-atomic resolution researchers could observe the ephemeral structure.

The researchers say that hemifusomes can help the formation of cellular vesicles, small bags that sail and combine material through the cell. They could also help form other organs composed of multiple vesicles, the study suggests. However, some evidence shows that hemifusomes do not participate in endocytosis, the traditional path in which cells swallow out external material.

“You can think of vesicles as little delivery trucks in the cell,” Ebrahim said in a statement. “The hemifusome is similar to a loading dock where they connect and transfer a cargo. There is a step in the process we didn’t know there was.”

Despite their fluent nature, hemifusomes are not uncommon. They appear to be surprisingly common in some parts of cells, particularly close to the cell membrane.

However, scientists are not exactly sure how or why hemifusomes form and then disappear. They hope to find out – as well as understanding what happens when hemifusomes fail to work correctly. Problems about how cells treat load is at the root of many genetic disorders.

“This is just the beginning,” Ebrahim said in a statement. “Now that we know that hemifusomes exist, we can start asking how they behave in healthy cells and what happens when things go wrong. This could lead us to new strategies to treat complex genetic diseases.”