For the first time, archaeologists got a detailed look at the complicated tattoos on a 2,000-year-old ice mummy, found buried deep in the permafrost-covered mountains of Siberia.

These tattoos would be difficult to produce even today, say the researchers, suggesting that ancient tattoo artists possess considerable skill.

With the help of modern tattoo artists, an international team of researchers examined the mummy’s tattoos in unprecedented details and identified the tools and techniques that ancient societies may have been used to create bodily art. The findings were published in the newspaper Antique.

As it is now, you have a common practice in prehistoric societies. Studying the practice, however, is difficult, as skin is rarely preserved in archaeological remains.

The “ice cream” of the Altai Mountains, in Siberia, is a remarkable exception they were buried in rooms now inserted in a permafrost, sometimes keeping the skin of these.

The Pazyryk people were horse-riding nomads who lived between China and Europe. “The Pazyryk Tattoos Culture – Iron Old Pastorators of the Altai Mountains – have long played archaeologists for their elaborate figurative projects,” Gino Caspar, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoantropology and the University of Bern, said in Emaileiled.

Scientists were unable to study these tattoos in great detail due to limitations in imaging techniques. Many of these tattoos are invisible to the naked eye, meaning that scientists did not know that they were there when the mummies were initially excavated in the 1940s.

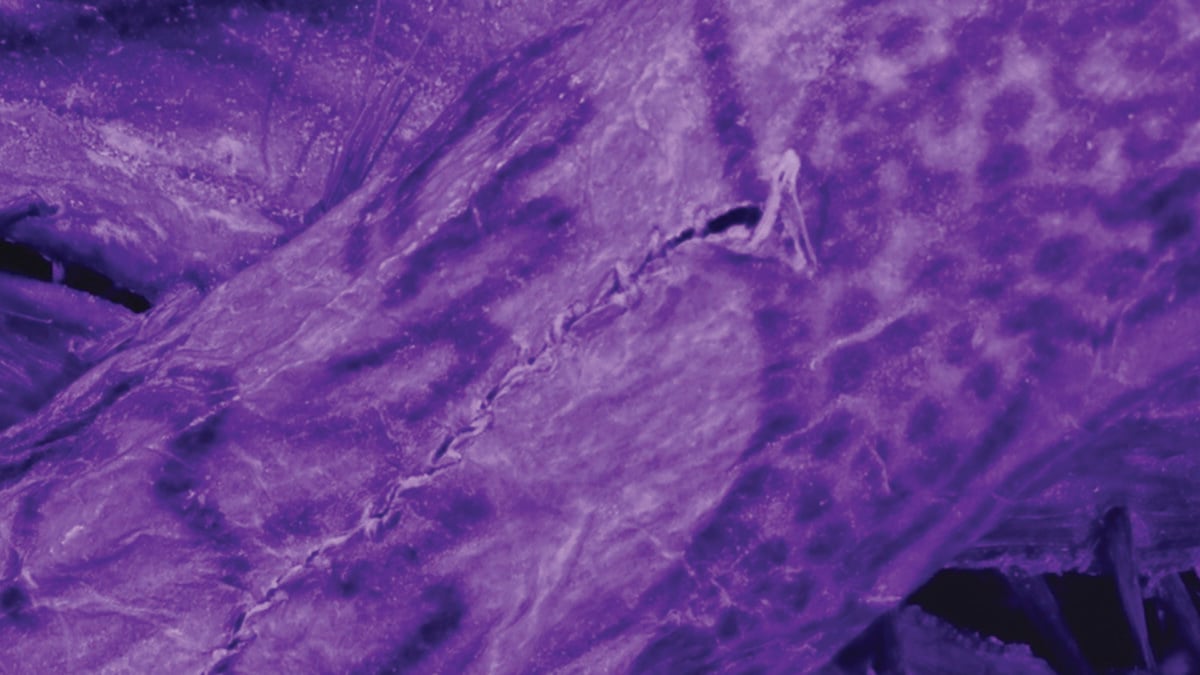

Researchers need infrared imagery to make ancient tattoos visible because skin melts over time, and the colors of the tattoos wither and bleed into the surrounding skin, making them weak or invisible to the naked eye. Infrared light, with its longer wavelengths compared to visible light, penetrates deeper into the skin and reveals what lies below the surface. So, so far, most studies have been based on drawings of the tattoos, instead of straight images.

But advances in imaging technology eventually allowed researchers to take high resolution images of the mummies and their tattoos. The researchers used high-resolution digital near-infrared photography to create a 3D scan of the tattoos on a 50-year-old woman of the iron age, whose preserved remains are housed at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Artistic depictions of the newly discovered tattoos reveal detailed tattoos of leopards, stags, chickens and mythical half-lion, a half-agitated being.

The researchers found that, like many modern people, the tattoos on the mummy’s right arm are much more detailed and technical than those on the left. This suggests that the two different ancient tattoos, or the same tattooist after they broke their skills, were responsible. The scanners also suggest that the artists used several tools – with one or multiple points – and that the tattoos were finished during multiple sessions.

This suggests that tattoo was not just a form of decoration in Pazyryk culture but a clever craft that required building skills and technical ability. Many other individuals were buried at the same location, indicating that tattoo was probably common practice.

“The study offers a new way of recognizing a personal agency in prehistoric bodily modification practices,” Caspari said in a statement. “Tattoo appears not only as a symbolic decoration but as a specialty craft – one that required technical skill, aesthetic sensitivity and formal training or apprenticeship.”