BBC

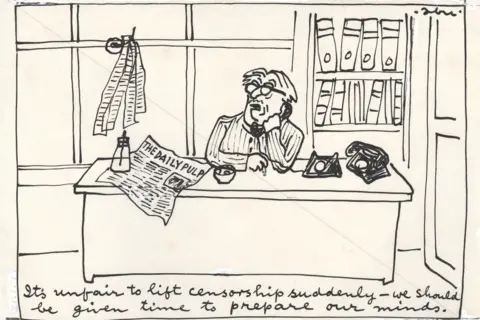

BBC“It is unfair to suddenly lift the censorship.” a grey newspaper editor snarled, a copy of the daily pulp scattered on the table. “We should have time to prepare our minds.”

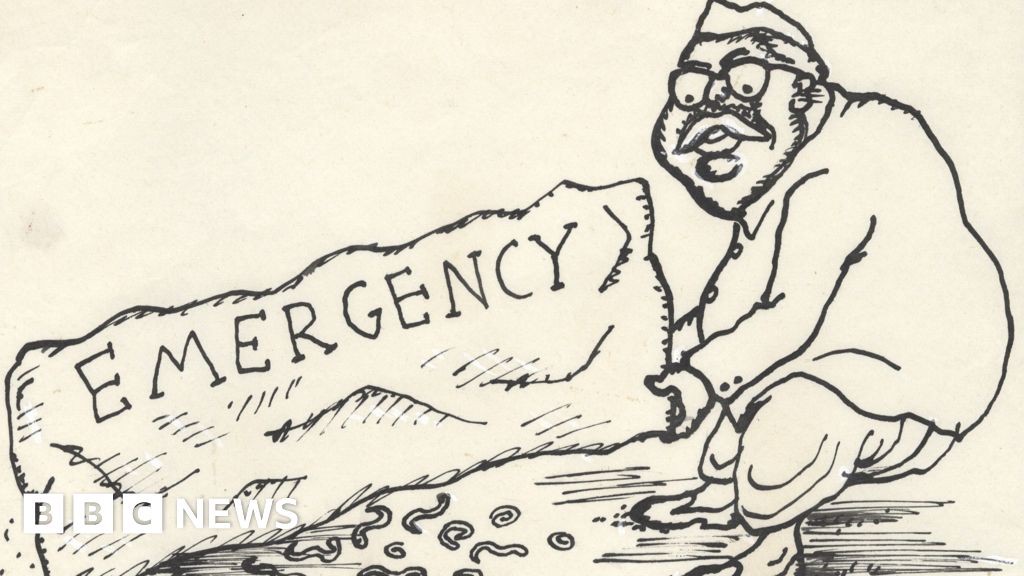

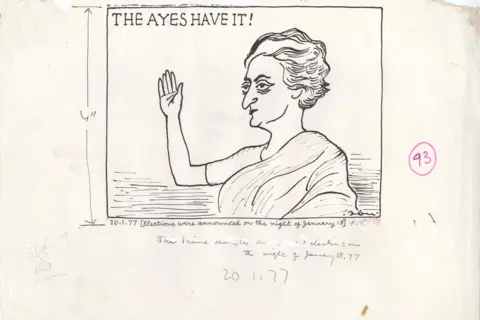

The cartoon that captures this moment – harsh and ironic – is the work of Abu Abraham, the best political cartoonist in India. His pen strung with grace and edges, especially in Emergency in 1975under Indira Gandhi, there were 21 months of civil liberties and media suspended the media.

On June 25, the press stayed overnight. The newspaper media in Delhi lost power and censorship in the morning. The government demands the press to succumb to the will – opposition leader LK Advani later famously said that many people “choose to crawl”.

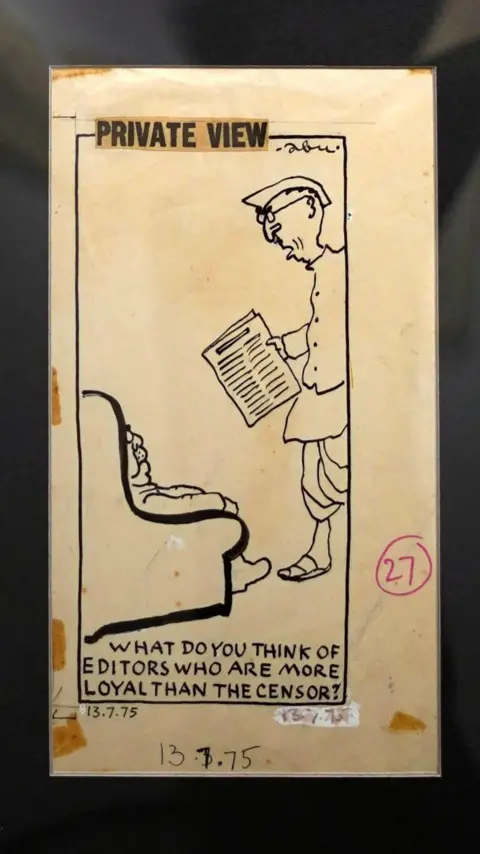

Another famous cartoon – who signed Abu under his pen name – Since then, one man asked another: “What do you think of editors who are more loyal than examiners?”

In many ways, half a century later, Abu’s comics are still real.

Current ranking in India World Press Freedom Index 151compiled by journalists without borders every year. This reflects Growing attention About media independence under the Prime Minister of Narendra Modi’s government. Critics say pressure and attacks on journalists, acquiescent media have increased the room for opposition voices to shrink. The government dismissed these claims, insisting that the media remained free and vibrant.

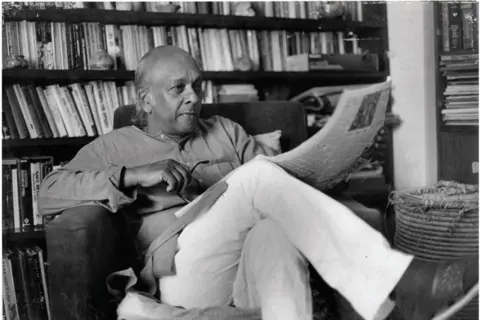

In London, painting cartoons for observers and guardians for nearly 15 years, Abu returned to India in the late 1960s. He joined the Indian Express as a political cartoonist while the country was fighting strong political turmoil.

He later wrote that the censorship—which required newspapers and magazines to submit news reports, editorials and even advertisements to government examiners before publication—begins two days after the emergency was declared, cancelled from a few weeks later, and then restarted a year later, before continuing a shorter period.

“I didn’t have formal intervention for the rest of the time. I was reluctant to investigate why I was allowed to move forward freely. And I wasn’t interested in finding out.”

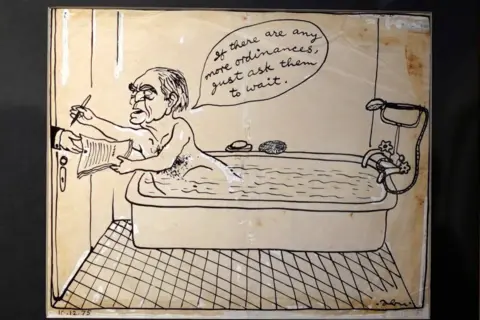

Many of Abu’s emergency cartoons are iconic. One person shows that then President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signed the declaration from his bathtub, capturing the haste and leisurely nature (Ahmed signed the emergency declaration issued by Gandhi before midnight on June 25).

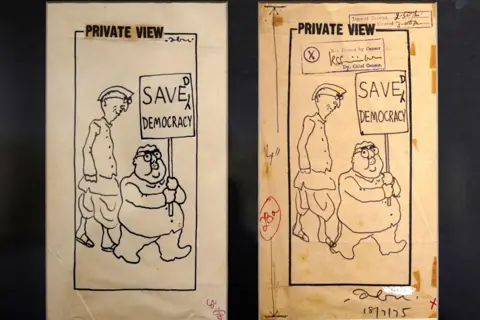

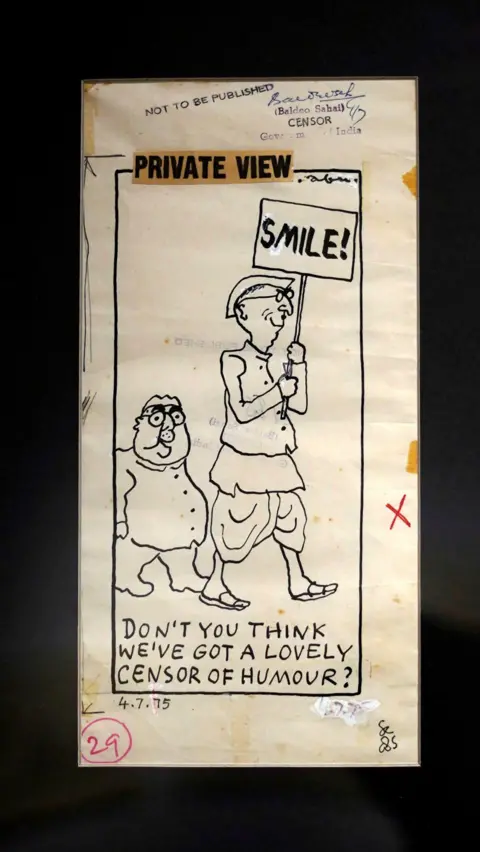

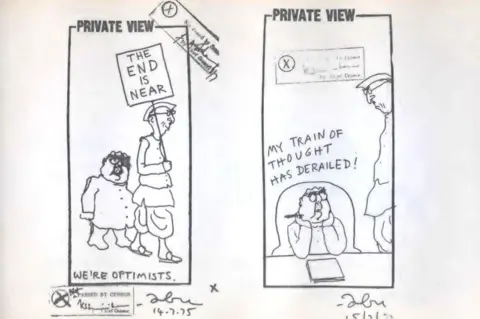

Among Abu’s eye-catching works, several comics are boldly stamped with the words “failed to the examiner”, a distinctive sign of formal suppression.

In one person, a man holds a placard with the words “Smile!” – In an emergency, the cunning poke of the government’s mandatory active movement. His companion Deadpans: “Don’t you think we have a lovely humorous examiner?” – a core that cuts off the country’s forced cheer.

Another seemingly harmless comic shows a man sighing at his desk, “My thoughts are derailed.” Another protester with protesters, with the sign “Save Democracy” written on it – “D” added awkwardly to the top, as if democracy itself is an afterthought.

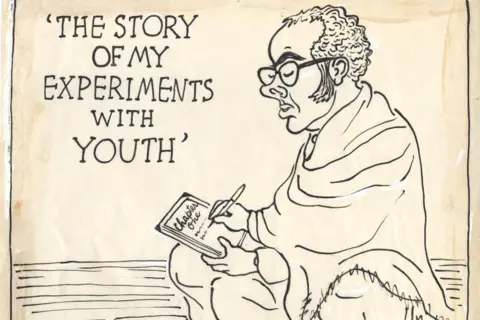

Abu also targeted Indira Gandhi’s unelected son, Sanjay Gandhi, who believes in running a shadow government in an emergency, wielding unrestricted power behind the scenes. Sanjay’s influence is both controversial and worrying. He died in a plane crash in 1980 – four years before his mother Indira was assassinated by her bodyguard.

Abu’s work is political. “I came to the conclusion that there is nothing non-political in the world. Politics is just anything controversial, everything in the world is controversial,” he wrote in the 1976 seminar magazine.

He also lamented the state of humor when the press was blocked – nervousness and creation.

“If cheap humor can be made in factories, the public will be anxious to line up in our ration shops all day. As our newspapers become more and more dull, readers, readers drowned in boring jokes, every joke. Rest assured,” Abu wrote.

In the 1977 Abu Abu mocking column, Abu mocked the culture of political flattery, the fictional statement of the conference of “all-Indian slave society.”

The fictional president of the society declared: “The real Nice Five is apolitical.”

The ironic monologue continues to cited mock statements: “Having a long and historical tradition in our country…’ Self-slavery is our motto.”

Abu’s imitation ultimately led to a guiding vision of society: “Touch all available feet and promote a wide range of flattery programs.”

Born in 1924 at attupurathu Mathew Abraham, in Kerala, southern Kerala, Abu began his career as a journalist in the nationalist Mumbai Chronicle, rather than an obsession with the power of printed words rather than an ideology.

His year of coverage coincides with India’s dramatic journey of independence, which is a joy to witness firsthand the joy of Mumbai (now Mumbai). He later reflected on the press and later pointed out: “There is a crusader in the press, but is usually a retainer of the status quo.”

In Shankar’s Weekly, a famous satirical magazine, Abu turned his attention to Europe. In 1953, a chance encounter with British cartoonist Fred Joss pushed him to London, where he quickly made his mark.

His virgin comic was accepted by Punch within a week after his arrival and was praised by editor Malcolm Muggerridge as “charming”.

In the London competitive scene, two years of freelance work, Abu’s political comics began to appear on Tribune, quickly attracting the attention of observer editor David Astor.

Astor provided him with paper employee positions.

He told Abu, “You are not as cruel as other cartoonists, and your job is the kind I want.”

In 1956, at Astor’s suggestion, Abraham adopted the pseudonym “Abu”, writing later: “He explained that any Abraham in Europe would be considered Jewish and my comics would be tilted for no reason, and I was not even Jewish.”

Astor also assured him of creative freedom: “You will never be asked to draw a political cartoon to express your thoughts that you do not personally sympathize with yourself.”

Abu worked for the Observer for 10 years, then worked for the Guardian for three years before returning to India in the late 1960s. He later wrote that he was “bored” by British politics.

Apart from comics, Abu served as a nominee member of the Indian House of Lords from 1972 to 1978. In 1981, he launched Salt and Pepper, a comic that ran for nearly two decades, blending gentle satire with everyday observation. He returned to Kerala in 1988 and continued to paint and write until his death in 2002.

But Abu’s legacy is never about a punch – it’s about the deeper truth that his humor reveals.

As he once said: “If anyone notices the decline in laughter, the reason may not be the fear of ridicule authority, but the feeling of reality, fantasy, tragedy and comedy is confused in some way.”

This absurdity and the ambiguity of truth often makes his work an advantage.

He wrote in the emergency: “The Joke of the Year Award is the Indian News Agency reporter who should go to London, and he carefully quoted comments from British newspapers about India in the emergency, “The train is running in time” – not realizing that it is a standard English joke on Mussolini’s Italy.

Abu’s comics and photos, courteous Ayisha and Janaki Abraham