Sondeep Shankar/Getty Images

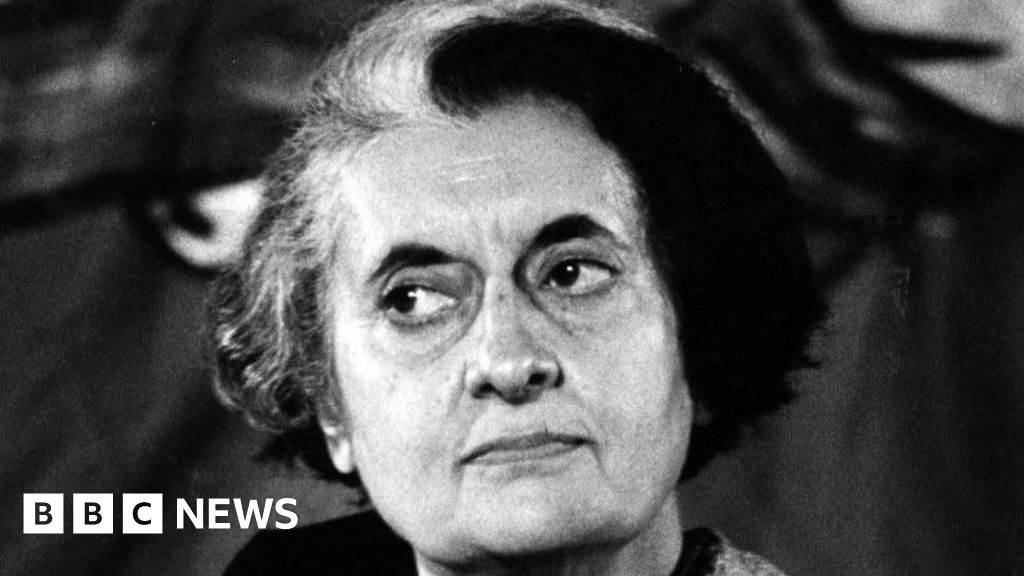

Sondeep Shankar/Getty ImagesIn the mid-1970s, India entered a period of suspension of civil liberties, led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi solicited emergency situations, with most of the political opposition being sentenced to jail.

Historian Srinath Raghavan reveals behind the scenes of this authoritarianism in his new book, and her congressional administration quietly begins to reimagine the country – not a democracy rooted in stopping and balancing, but as a centralized country commanded and controlled.

During Indira Gandhi and years of changing India, Professor Lagawan showed how Gandhi’s top bureaucrats and party loyalists began to push the presidential system – focusing executive powers on executive powers, which are side jobs that “hinder” the judiciary and reduce parliament to symbolic chorus.

Partly inspired by Charles De Gauler Francethe push for a stronger presidency in India reflects a clear ambition that even the shackles of Congress democracy are beyond limits – even if it has never been fully realized.

Professor Raghawan wrote that in September 1975, BK Nehru, then an experienced diplomat and Gandhi’s close aide, wrote a letter calling the emergency “a huge courage and power of popular support” and urged Gandhi to seize the moment and it all began.

Nehru wrote that parliamentary democracy “cannot provide answers to our needs.” In this system, executives are constantly dependent on the support of the elected legislature “is seeking universality and stopping any unpleasant measures.”

Nehru said India needs a direct elected president – free from the dependence of parliament and able to take “firm, unpleasant and unwelcome decisions” in the national interest.

The pattern he pointed out was Charles de Gaulle’s France – focusing its strength during a strong presidency. Nehru imagines a single, seven-year presidential term, proportional representation in parliamentary and state legislatures, the judiciary restricts power and is required by strict defamation laws. He even proposed the disenfranchise of fundamental rights – the right to enjoy equality or freedom of expression, such as their feasibility.

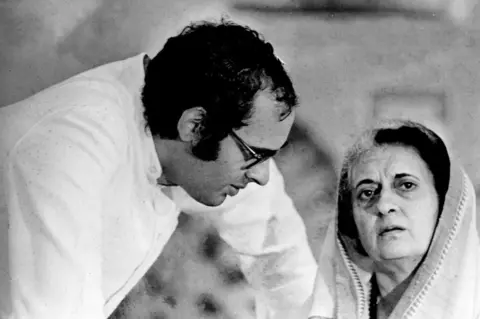

Nehru urged Indira Gandhi to “make these fundamental changes to the constitution now when you have a two-thirds majority”. His idea was “received” by Prime Minister’s Secretary PN Dhar. Gandhi then gave Nehru the approval to discuss the ideas with her party leader, but “very clear and stressed” that he should not convey the impression that they had the impression she recognized.

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Images

Sondeep Shankar/Getty ImagesProfessor Ragawan wrote that the ideas were enthusiastic support from senior Congress leaders such as Jagjivan Ram and Foreign Minister Swaran Singh. The Chief Minister of Haryana state is outspoken: “Get rid of the nonsense of this election. If you ask me, please let our sister (Indira Gandhi) lively president without doing anything else”. M Karunanidhi of Tamil Nadu (one of two non-Parliamentary Chief Ministers) was not impressed.

Professor Lagawan wrote that when Nehru reported back to Gandhi, she still did not trade. She directed her closest assistant to explore the suggestions further.

What appeared was a document called “New Look to Our Constitution: Some Recommendations” which was kept confidential and circulated among trusted consultants. It proposes a president with power that is even bigger than his American counterparts, including controlling judicial appointments and legislation. The new “Judicial Superior Council” chaired by the president will interpret “Law and Constitution”, which actually sterilizes the Supreme Court.

Gandhi sent this document to Dhar, who recognized that it “distorted the constitution in an ambiguous direction of autocracy.” Congress President DK Barooah has made a public call for a “thorough re-examination” of the Constitution through a public appeal at the party’s 1975 annual meeting.

This idea has never completely crystallized into formal advice. But its shadow lingers The 46th Amendmentadopted in 1976, expanded parliamentary powers, limited judicial review and further concentrated the administration.

The amendment passed the super tribute from five to seven judges, aiming to dilute the constitution and thus enact the law more severely. “Basic Structure Theory” That limited parliamentary power.

It also handed the federal government the deployment of armed forces in the states, declared emergency situations in specific areas, and extended the presidential rule – direct federal rule – from six months to one year. This also frees the election dispute from the judiciary.

It’s not a presidential system yet, but it carries its genetic imprint – strong executives, marginalized judiciary and weakens responsibility for checks and balances. The politician newspaper warned: “By passing a positive stroke, the amendment tilts the constitutional balance to support parliament.”

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Images

Sondeep Shankar/Getty ImagesMeanwhile, Gandhi’s loyalists went all out. Defence Minister Bansi Lal urged her to serve as prime minister, while MPs in the northern Haryana, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh unanimously called for a new constitutional conference in October 1976.

Professor Lagawan wrote: “The Prime Minister was shocked. She decided to reject these moves and speed up the passage of the Parliamentary Amendment Bill.”

By December 1976, the bill had been passed by both houses of parliament and approved by the 13 state legislatures and signed into law by the President.

After Gandhi’s shocking defeat in 1977, the brief Janata party – a pieced together by anti-Gandhi forces – quickly undoes the damage. pass Forty-three and Forty-four The amendment, which backed the key part of 40 seconds, abolished the dictatorship and restored democratic checks and balances.

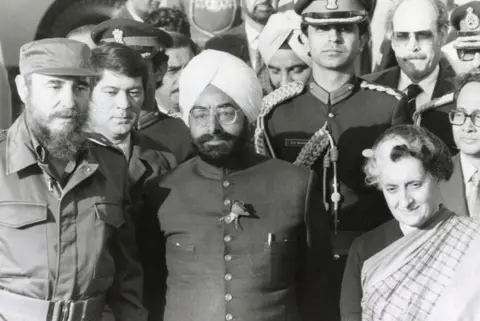

Gandhi returned to power in January 1980 after the Janata government collapsed due to internal divisions and leadership struggles. Strangely, two years later, the party’s famous voice once again raised the idea of a presidential system.

In 1982, with the end of President Sanjiva Reddy’s term, Gandhi seriously considered resigning as prime minister to become President of India.

Her chief secretary later revealed that she was “very serious” in the move. She was tired of carrying Congressional gatherings on her back and seeing the president as “a way to give new stimulus measures to be given by her party in shock.”

Finally, she backed off. Instead, she promoted loyal interior minister Zail Singh to president.

Despite the serious flirting, India has never moved towards a presidential system. Gandhi, a deep tactical politician, stopped himself? Or is there no country’s appetite for major changes, and India’s parliamentary system proves to be sticky?

Images by Getty Gamma-Rafe

Images by Getty Gamma-RafeAccording to Professor Raghawan, in the early 1970s, the implication of the president’s drift was that India’s parliamentary democracies (especially after 1967) became more competitive and unstable and characterized by fragile alliances. Around this time, the voice began to suggest that the presidential system might be more suitable for India. The moment when the emergency becomes these ideas crystallize into serious political thinking.

Professor Raghavan told the BBC: “The aim is to reshape the system in a way that immediately strengthens her power. Without a long-term design – most of the lasting consequences of her (Gandhi) rule are likely to be unexpected.”

“In an emergency, her main goal is short-term: to keep her office free from any challenges. The Forty Second Amendment was formulated to ensure that even the judiciary cannot hinder her way.”

The itch of the presidential system within Congress has never completely disappeared. Until April 1984, Senior Minister Vasant Sathe launched a nationwide debate advocating for the shift to presidential governance, even in power.

But six months later, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikhs in Delhi, and with her, the conversation suddenly passed away. India maintains parliamentary democracy.